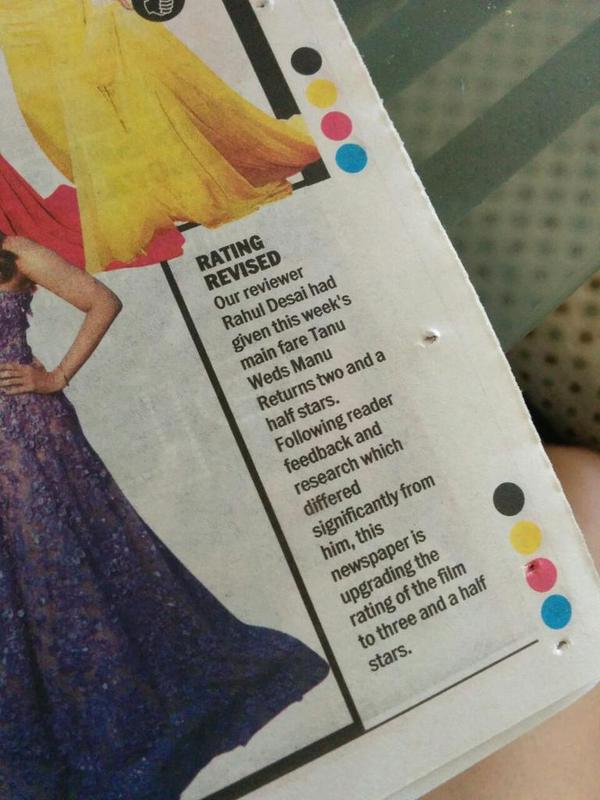

The Mumbai Mirror retraction.

This startling announcement about the two-and-a-half star Tanu Weds Manu Returns was buried at the bottom corner of one of the entertainment pages, below the hemlines of gowns spotted at the Cannes Film Festival. It didn't take long for alert readers and journalists to upload images of this item on Twitter. They proceeded to attack the newspaper, declaring their solidarity with Rahul Desai, who has become India's best-known critic in the course of a single day.

The decision to disown its freelance movie critic’s opinion is not entirely surprising. Mumbai Mirror is published by Bennett and Coleman Company Limited, which has a unit called Optimal Media Solutions (formerly known as Medianet) that allows advertisers to pay for press releases and other publicity material to be published in The Times of India's daily entertainment supplement without being clearly labelled as advertisements. It has become a routine practice for movie production companies to publicise their releases this way.

Tanu Weds Manu Returns has been co-produced and distributed by Eros Entertainment, and it has made enough money to please film-business insiders dismayed by the recent Bombay Velvet debacle. Significantly, Eros Entertainment did not advertise in the Bombay Times and related supplements across the country for Tanu Weds Manu Returns. Since the production has conquered audiences without any help from this marketing machine, it isn't only film critics who are anxious about what the future holds.

It isn't clear whether such U-turns and acts of self-censorship will become more frequent. What is clear is that even though we live in an age where one-line assessments of movies appear on social media within minutes of the opening credits at a premiere, the professional opinion of the movie critics continue to matter. Or, to be specific, the bar on top of a review that enumerates the critic’s rating in terms of stars.

Starry starry days

Every professional movie critic has had this conversation. You return after a movie preview and run into a colleague or a neighbour. You tell them where you were a few hours ago and pat come the question, “How many stars?”

Hindi cinema is ruled by not one but two star systems. The first is bad enough, because it means suffering through films that would have benefited from thoughtful actors rather than just desirable bodies. But the other is just as tedious, since it necessitates a quantitative judgement being delivered along with a qualitative one. The film review has been reduced to a series of five-cornered symbols that get far more attention than the critic’s attempts to unpack a film’s themes, narrative treatment, performances, music and whatever else makes up the package.

On a scale of one to five, if a movie reaches three, it is home. The “two-and-a-half” business causes heartburn among newspaper page designers who have to shade one half of the star, but is a feeble attempt to rescue a film from the fires of the two-star hell and accord it some redemptive qualities.

The perfectly scripted and smoothly directed movie that clicks from start to finish is a rare occurrence. Many movies are an agreeable mess, with some convincing passages and other weak sections. A well-argued review will consider various narrative aspects and eliminate the need for reductive thinking. Yet, the people involved in marketing and distributing films need rating stars because they look good in publicity material and on hoardings, and are the most effective way of reinforcing the production’s claim to artistic credibility. Potential moviegoers too find that a rating system helps them make up their minds faster, and few are willing to pore over the critic’s clever wordplay or pontifications.

Trading places

Ratings especially matter in an age that values economic success as the only kind of achievement that matters. The Mumbai Mirror kerfuffle demonstrates how the movie review has come to be conflated with the trade report. In an ideal world, critics would weigh a film’s merits and demerits while trade analysts would predict its commercial prospects. The review surveys while the trade report makes predictions.

However, commerce is inherent in show business. Movie reviews clearly attempt to influence purchasing power, best expressed in the dreadful exhortation, “Do yourself a favour and watch this one.”

Critics also get asked, “Will the film run?” The question looms larger than ever before. The cost of producing films has risen enormously, and there is tremendous pressure on new releases to reel in movie audiences in the very first week so as to recover expenses. Producers spend vast sums on pre-release marketing (and pay for plugs in Bombay Times and its equivalents around the country), so the only kind of publicity they care for is the shiny and happy kind.

The bottom line

The embrace of a return-on-investment mentality that is closer to Dalal Street than Film City has also influenced entertainment journalism. From the number of stars a movie is given to the crores it earned during its opening week, there is an increasing interest in the commerce side of a film production. Apart from gossip, interviews and movie previews, reporters on the entertainment beat are also expected to have a head for box-office numbers. Trade analysts who churned out telegraphic prose for magazines that circulated mostly in movie business circles in the past are now highly regarded for their ability to predict a movie’s fortunes. The aura of movie stars now includes the knowledge of how many crores each of them is worth.

It’s only a matter of time before publishers decide that celebrities who are cash cows must also be treated as holy cows. In the new, hyper-commercial world, independent-minded critics are a thorn in the side of movie producers. The easiest way to discredit critics is to claim that they are out of touch with popular taste and are unable to gauge the movements on the ground from their ivory towers. An even easier way to show reviewers their place is to bend the ears of their bosses. Filmmakers cannot control Twitter users and WhatsAppers, and cannot fault the nameless audiences who fail to swell cinema halls (recent case in point: Bombay Velvet). But they can pick up the phone and rant to a publisher about a critic who dared to point out the emperor’s lack of attire.

Hindi cinema has countless examples of movies that worked despite withering reviews as well as titles that only reviewers loved. The complaint that critics have failed to accurately explain a filmmaker's work to audiences is never heard when the number of stars rank between three and five. Some old-fashioned producers even joke that the greater the stars, the more likely a movie is to tank.

Filmmakers are quick to attack critics when they taste failure. But it is the rare producer who looks at the five-star ratings in the first column and the sub-zero earnings in the second column and admits the truth of the Hollywood adage about why some become blockbusters: “Nobody knows anything.”