In India, the onion is more than just a vegetable. Apart from being a diet staple and hoarder’s favourite, onion prices are often used as an indicator of inflation – and the attendant anger aimed at the government in charge. Earlier this month, onion prices once again hit the roof as the bulb was reportedly being sold at around Rs 80/kg in the national capital after the total production fell last year.

While the Congress and other parties lined up to protest against the ruling National Democratic Alliance led by the Bharatiya Janata Party, Delhi government started selling onions at around Rs 40/kg through public distribution outlets and government milk booths in the capital.

Meanwhile, the central government sought to clarify that it is taking measures to curb prices by putting limits on onion stocks that can be held at any given time and hiking up the minimum price at which onions can be exported to increase supply in the domestic market. The government added that the price rise was due to the fall in production in the year 2014-'15.

“Prices of onions have been rising on account of a decline in total production from 189.23 lakh tonnes in 2014-15 as against 194.02 lakh tonnes in 2013-14 i.e. a decrease of 4.79 lakh tonnes,” a press release said.

That, however, is only one aspect of the story.

Climbing production

Even though production fell last year, onion produce in the country has rapidly grown over the last few years as visible from the above chart. It has risen from 136 lakh tonnes in the year 2008-'09 to more than 180 lakh tonnes in 2014-'15. Add to it the fact that the crop is planted thrice a year which should ensure that there are more onions than needed in the market at any given point.

In fact, India has emerged as one of the major exporters of onions in the world. More than 5,20,000 tonnes were exported by India in the three-month period between April-June in 2013.

Spiralling prices

Even then, prices of onions have more than tripled in wholesale markets. This spike, when added to retailers’ margins, often make onions unaffordable for the final consumer. From there, it doesn’t take long for an upward price spiral to begin that results in hoarding and even theft of thousands of kilograms of onions.

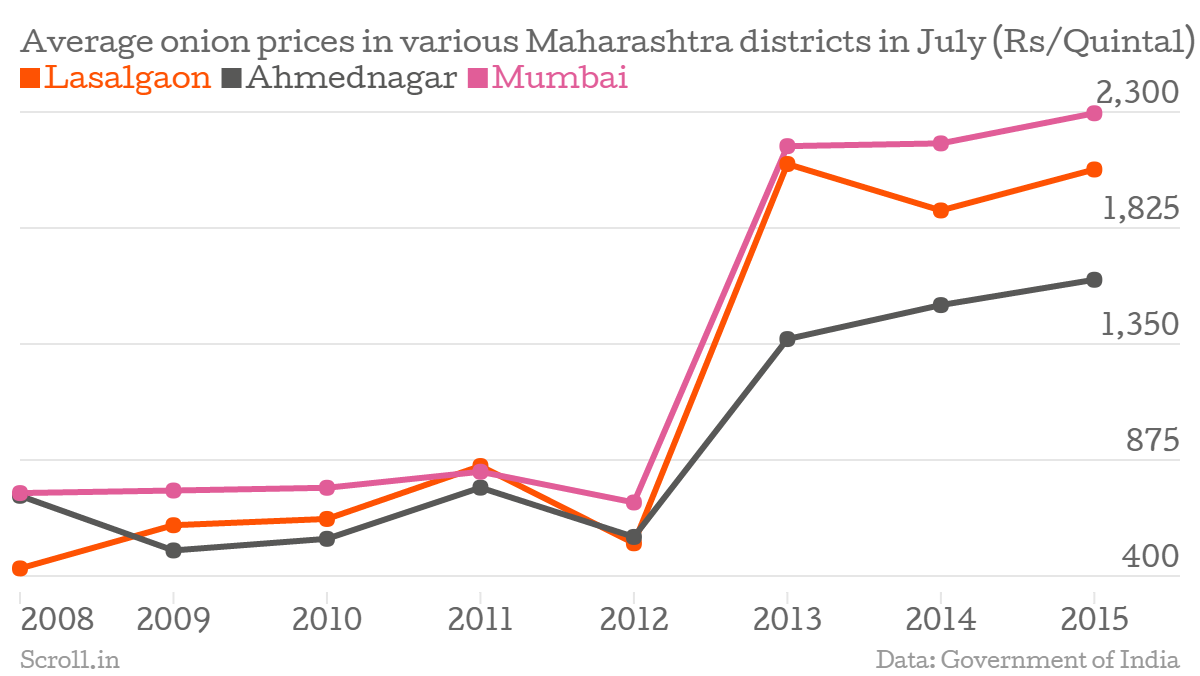

The above graph compares and tracks the rise in average wholesale prices for onions in three different districts in Maharashtra, the state which accounts for almost one-third of all onion produced in the country. To be sure, some smaller mandis show huge price variation depending on demand and market structure, but average prices reveal a steep upward curve in onion prices which coincides with increased production.

In this scenario, it is worth asking the question that why are prices still rising if we have enough onions being produced and inflation was at a record low of 3.7% in July?

Hoarding by traders looking to cash in on price spiral, is a common answer. However, there are more things in play here than just greedy traders.

Post-harvest loss

We might be producing enough onions but a significant quantity from the stock never makes it to mandis because of various post harvest losses which usually occur due to diseases. The situation is further exacerbated by a lack of reliable infrastructure across markets that can keep the produce safe until it is taken to the mandis.

The loss, occurring post harvest, is believed to be as much as 25%-30% for onions according to a research paper titled “Indian onion scenario” produced by the National Council of Applied Economic Research last year.

“Physical injury during and after harvest, greening of onion due to exposure to sunlight, sprouting and injuries during storage due to ammonia, controlled-atmosphere storage, and freezing also cause post harvest losses,” it noted. The paper added that absence of storage facilities result in various diseases such as bulb rot or bacterial rot which end up greatly reducing the quantity and quality of onions.

Tightened supply

In 2012, the Competition Commission of India commissioned a full-fledged assessment of the onion wholesale markets in Maharashtra and Karnataka to gauge the extent of trader-supplier nexus in the markets which often ends up dictating the prices.

The report revealed that not only such nexuses exist and thrive in the markets, the reason behind price rise could well be the lack of competition in the markets as big players dominate in the wholesale markets instead of independent farmers or small traders who could keep the prices in check by ensuring multiple supply sources.

Instead, the study argued, price rises were largely artificial and due to big traders who are buying farm produce in bulk at cheap during the harvest season when farmers look to dispose off produce and earn some cash. Then, the traders try to tighten the supply through hoarding during the lean seasons for onion production.

“The lean season also happen to be coincided with start of major festivals and ceremonies like marriages in India,” the report noted. “This clearly manifests itself during months of September to January, in which the supply from onion producing regions is minimal and festivals like Dasera, Dipawali, Eid, Christmas and marriages and other ceremonies put higher pressure on the demand of onion.”

Opportunist retailers

It is not just the wholesale traders who are to be blamed for price rises every few years, the CCI study said. It found retailers in major towns and cities often inflating the price anywhere from 10-170% further adding to woes of consumers. However, they were found to be doing it largely when the wholesale prices were low and they could get away with their inflated prices.

As soon as the wholesale prices went up, the retailers were seen lowering their markups because the demand was already falling. Even then, they ended up earning a margin of 60-110%, the paper said.

“Even if we consider their marketing cost between 40% to 90%, their profit margin is still quite high,” it noted. “This is [a] peculiar problem originating from current market structure of onion in India. This clearly shows that along with traders, retailers also exploit the situation of crisis for their own benefits.

Poor information flow

Another study conducted by the National Institute of Agricultural Marketing in 2012 analysed the surge in onion prices in the year 2010 and confirmed that prices of onions were hardly related to production shortages.

It, however, highlighted that apart from curbing hoarding and building infrastructure, there is a need to forecast lean production cycles well in advance to plan for shortages instead of letting it become an opportunity for the hoarders.

It argues that in 2010, market situations were not forecasted well and hence, the government was not expecting such a steep price rise or even a supply shortage.

“The crop situations were not predicted timely and thus, the information on loss in production was not anticipated by market intelligence,” it said.

Hence, the report argues, the government should make much more efforts in integrating the farm information with the markets and take stock of the situation regularly so that production shortages don’t come as a shock.

“Proper staggered planting of onions with suitable varieties can address supply gap during the slack period, there by [thereby] stabilizing the prices across the year uniformly. As part of market reforms, implementing market intelligence systems can help in discovering the right prices for producers as well as consumers.” the study noted.